Recently, we did a close reading of Britney Spears’ autobiography to talk about showing versus telling. Today we turn to a different memoir, for a different topic. Today, we’re going to talk about voice.

What is voice? Writers and critics, professors and agents, teachers and editors all agree that it’s very important. But what is it, exactly? And how do you find your own?

Voice is how you sound on the page. It’s how you, the author, tell us who you are, and how your characters tell us who they are. It’s both locution (the words you use) and content (what you’re discussing). It’s whether you say don’t or do not, whether the references you drop are from Shakespeare and Proust or Taylor Swift and Beyonce. It’s whether you use short, declarative sentences, or whether you write in paragraphs that are long and elaborate and full of parentheticals and ellipses. Voice is what lets you know, after a single page, and sometimes, just a single paragraph, that you’re reading Raymond Carver, or F. Scott Fitzgerald, Jane Austen or Virginia Woolf. When it’s there, it’s as specific and identifiable as a fingerprint, and means your characters feel real, distinct from one another and the author. When it’s not – when a voice is bland, or undistinguished; when there’s a gap between how you’re expecting a character to sound and how they actually sound…then you’ve got problems.

A writer’s voice is made up of a thousand different things, a thousand difference choices – this word or that one? Contraction or no contraction? Add clauses, or divide a thought into two sentences? Curse words or no curse words? References to NASCAR or polo? Voice takes time to develop, and usually involves periods of intense imitation, where you read a ton of (insert favorite author here) and then start writing just like (insert favorite author here). It happens to every writer, and the only cure for it is time, and practice, and revision after revision, rewrite after rewrite, until you don’t sound like anyone but yourself.

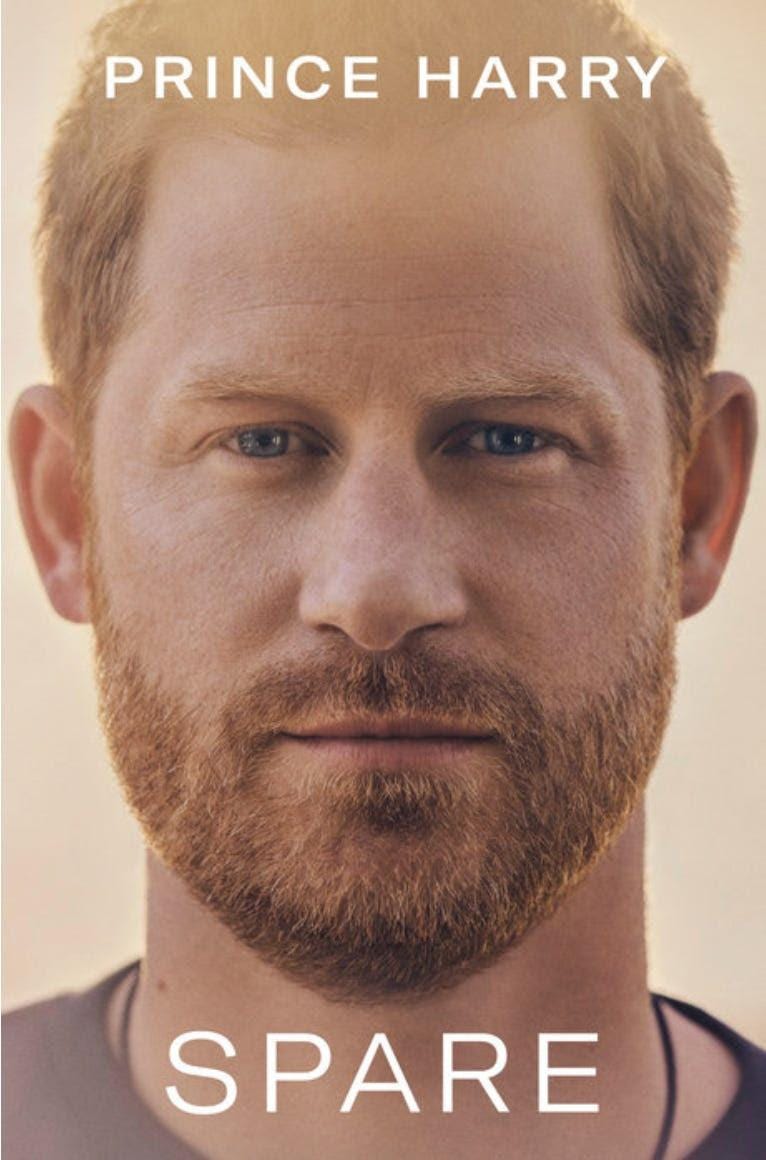

I thought it would be easiest to talk about voice in an instance where there’s a problem – where there’s a difference between how someone should sound and how someone does sound. And so we turn to a ghostwritten memoir.

What do we know about Prince Harry? He’s upper-class (obvs). He attended public schools (which is what they call private schools in England. Go figure). After finishing up at Eton – a school to which, he tells us, he would not have been admitted without family intervention – he went into the Army, where he served for ten years, flying helicopters in the Army Air Corp.

So: a wealthy, privileged guy, but not a super-educated one. Not (again, per Harry’s own admissions) especially bookish or academic. A young-ish guy. A British guy. A guy whose references are going to be informed by his time in the Army…and a guy who, we know, worked with a ghostwriter, a prizewinning and highly-regarded author named J.R. Moehringer. Who is American, college-educated, very well-read, and, at 58, some eighteen years older than Harry.

Like many, many Americans, I read Harry’s book because I wanted the hot goss; the inside scoop on what was going down in the Palace. I wanted the details that bring that rarefied world to life – the food, the furnishings, the people and the pastimes. On that count, the book more than delivers, starting with Harry’s descriptions of the yoga handstands his father, King Charles performs “daily, in just a pair of boxers, propped against a door or hanging from a bar like a skilled acrobat,” and how, “if you set one little finger on the knob you’d hear him begging from the other side: No! No! Don’t open! Please God don’t open!” You cannot make this stuff up, and it’s perfect in showing us who Charles is, what he does, how he sounds.

We hear all about Balmoral, and the Queen’s piper, serenading her with his bagpipes: “Rumpled, pear-shaped, with wild eyebrows and a tweed kilt, he went wherever Granny went, because she loved the sound of pipes, as had Victoria…while summering at Balmoral, Granny asked that the piper play her awake and play her to dinner.”

You know. As one does.

I read for gossip, and for details. I also read with a writer’s eye, trying to see if I could suss out what, if any, parts were Harry-authored, and which read 100 percent like someone else was at the keyboard.

Which meant I was reading for voice.

Imagine you’re a novelist, writing the character of a young, not-too-bookish British prince. What’s he thinking about? What words is he using? Then consider this passage, from the beginning of the book. Harry’s gone to England for his grandfather’s funeral. He’s in a garden where other noted Windsors are buried, waiting for a meeting – which turns into a showdown – with his brother and his father.

“Our feet almost on top of Wallis Simpson’s face, Pa launched into a micro-lecture about this personage over here, that royal cousin over there, all the once-eminent dukes and duchess, lords and ladies, currently residing beneath the lawn. A lifelong student of history, he had loads of information to share, and part of me thought we might be there for hours, and that there might be a test at the end.”

The sentiment seems completely Harry’s. The language – especially the sentence that begins “Our feet almost on top of Wallis Simpson’s face,” and words like residing instead of buried, or personage instead of person – feels more polished than I’d expect, but I’m still on board. Loads of information feels colloquial and youthful, and Harry’s fear that there might be a test feels specifically Harry-ish.

That passage works, in short, because you’re not hearing two voices. There’s no daylight between prince and scribe.

Moving on, we get this passage, the one that gave the book its title:

“The Heir and the Spare – there was no judgment about it, but also no ambiguity. I was the shadow, the support, the Plan B. I was brought into the world in case something happened to Willy. I was summoned to provide backup, distraction, diversion and, if necessary, a spare part. Kidney, perhaps. Blood transfusion. Speck of bone marrow.”

That’s a lovely sentence with a pleasing internal rhythm so subtle that you hardly notice the way it gradually darkens until you’ve reached the pitch-blackness of spare part. Watch the way the nouns work as a group, beginning with Backup. A backup seems fine. Who doesn’t need a backup? Distraction and diversion, ditto. Harmless, and also a familiar dynamic to anyone who’s ever had (or been) the overachieving older sibling who had (or was) the younger cutup. You’re bouncing along the sentence, and then you land – hard – at spare part…and then, at what strikes me as a very un-Harry-ish word.

Can you guess which one?

It’s speck. Speck of bone marrow. Speck doesn’t sound like a word a thirtysomething Brit would employ, or, necessarily, one that a fiftysomething American would use. It sounds, to my ears, at least, like a fiftysomething American trying to sound British and upper-crust-y. Pip, pip, cheerio! Jolly good, old chap!

If it had read a little bit of bone marrow, I wouldn’t have been jarred. Even just bit of bone marrow could have been, conceivably, Harry. But speck wasn’t the right word, IMO. It gave the game away.

Not that ghostwriting is an easy gig.

J.R. Moehringer wrote a fascinating piece for the New Yorker about his experience as Harry’s ghost, and the challenges of ghostwriting in general.

“Things,” Moehringer wrote, “can go sideways in a hurry. An author might know nothing about writing, which is why he hired a ghost. But he may also have the literary self-confidence of Saul Bellow, and good luck telling Saul Bellow that he absolutely may not describe an interesting bowel movement he experienced years ago, as I once had to tell an author. So fight like crazy, I say, but always remember that if push comes to shove no one will have your back. Within the text and without, no one wants to hear from the dumb ghostwriter.”

When you think about it, all ghostwriters have a hard job. A ghostwriter – any writer – is well-read and bookish, and, if I’m going to generalize, probably a thoughtful and introspective kind of person. Which is fine if the person hiring the ghostwriter is well-read, bookish, thoughtful and introspective. Except a thoughtful, well-read, bookish, introspective person wouldn’t necessarily need a ghostwriter. The people who do – your athletes, your celebrities, your occasional royal – are always going to have different references, difference experience, and are going to speak in a different voice than the person they hire to help them tell their stories. A ghostwriter’s job is disguising that difference, so you feel like you’re hearing the bold-named person’s voice, and not the voice of the person they’ve hired.

Tell me: have you read many ghostwritten books? Which ghostwriters do you think do the best job of sounding like their subjects?

And finally — do you want to talk about this live with me? I’ll be in the chat answering questions — a feature available to paid subscribers of The Inevitable Substack — Friday, May 17 from 2pm to 3pm ET. Hope to see you there!

I'm ghostwriting full-time now, and you're right; there's so much that goes into capturing the subject's voice. I record every word and I work almost exclusively from the transcripts so they sound like themselves. I'll say this about Britney's ghost--he wasn't paid enough, no matter how much he received. I'll always choose a CEO's book over celebrity because every ghost knows the "cool" factor of being with celebs wears off quickly. And I'm learning that all of us have to deal with the "I never said that" argument, despite the subject being on audio AND video.

not every memoir admits to be ghost written - till something hits the fan (hello kristi noem). there are times that i feel the book has been ghost written, but it's hard to know.