One Quick Look as Each of 'em Leaves You

On watching "Doctor Who" with a soon-to-be-empty nest

Starting back in elementary school, Phoebe, my younger daughter and I, have watched a television show together.

On nights when she’s here, and not at her father’s, and doesn’t have too much homework, or other things going on, she’ll ask, “Want to watch a show?” and we’ll assemble in the TV room at 8:30.

Over the years, we’ve done all of “American Horror Story, and “Community,” and “What We Do In the Shadows” and “Brooklyn 99.” We’ve done “The Haunting of Hill House” and “Bly Manor” and “The Midnight Club” and “The Fall of the House of Usher.”

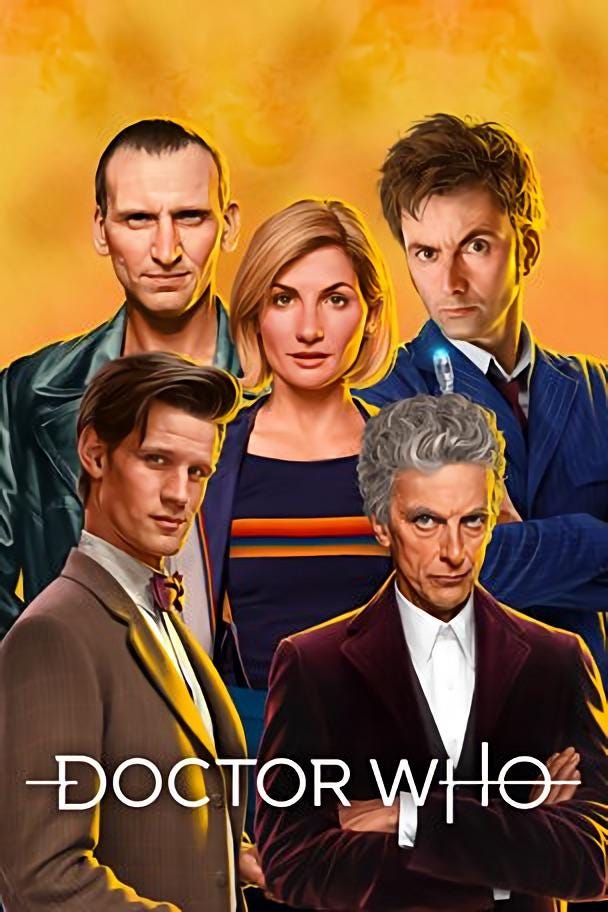

And now, we’re working our way through the reboot of “Doctor Who.”

Phoebe will sit on the love seat, with her favorite purple Slanket. I’ll be in the recliner, with my favorite woven Pottery Barn blanket. Bill will be on the couch.

Levon will visit with each of us, usually with an interlude of ardently licking Bill’s hands and his feet.

By nine o’clock or so, Bill will make some announcement about how Doctor Who is out of network for him. He’ll go upstairs, Levon will curl up with Phoebe, and we’ll finish the episode together.

If you’re unfamiliar, briefly, “Doctor Who” is a science fiction/adventure/humor/horror hybrid that began in Great Britain in 1963 and was rebooted in 2005.

The central conceit of the show is that there’s this Doctor – the last of a race called the Time Lords – who travels the universe in a TARDIS, which is basically a spaceship/time machine disguised to look like a blue police box. Typically, the Doctor plucks a human companion from the ranks of the British citizenry (he’s especially fond of whisking women away on, or just before, their wedding days). Sometimes, the companion is in love with the Doctor. Sometimes, it’s a strictly platonic relationship. Always, the companion is the Doctor’s conscience. She’s the one who keeps him humble, who speaks up for the virtues of humanity.

The doctor and his companion travel the whole of space and time. Sometimes, they answer distress calls from the humans or aliens who know how to reach out for some interplanetary help (Winston Churchill, it turns out, is among them). They have adventures. They meet vampires in Venice, and Shakespeare in London; Queen Victoria and Charles Dickens, Agatha Christie and Vincent Van Gogh. They encounter all manner of aliens: the Ood, the Judoon, the Slitheen, the Face of Bo. They meet Silurians and cyborgs and Cassandra, the last of the humans, who is basically a morsel of skin with eyes and a mouth who’s been stretched, trampoline-style, on a metal frame and gets wheeled about, demanding to be moisturized.

And they face off against enemies including the Daleks, who look sort of like extra-large, pyramid-shaped R2D2s ornamented with deadly plungers who wheel around repeating “EXTERMINATE. EXTERMINATE!” in robotic voices.

Trust me, it is scarier than it sounds.

The doctor’s deal is that he’s basically immortal. Actors, of course, are not. So, every season or two, the Doctor will face some terrible peril or have to make some unthinkable sacrifice. But, instead of dying, he regenerates, getting an entirely new body and new face.

Phoebe and I started off with the Ninth Doctor, played by Christopher Eccleston, who traveled with Rose Tyler, a shopgirl from the estates. She’s with him when Doctor sacrifices himself to save her, and regenerates into the Tenth Doctor, played by David Tennant.

He eventually leaves Rose in a parallel universe, with a Time Lord/human hybrid, a version of himself, who will grow old alongside her. Martha Jones, who follows Rose, travels with him until she decides she can’t remain in a one-sided romance with a being who can’t love her back. She decides to go home. The Doctor then hooks up with Donna Noble, who is decidedly NOT in love with him. She’s his best friend. And when he has to wipe her memory to ensure her survival, it’s heartbreaking.

The show does a fair bit of hand-waving at the “timey-wimey wibbly-wobbly” stuff; the issues caused by messing with past and with future, or having multiple versions of yourself popping up, and entire story arc about an attempt to kill Hitler, which doesn’t go well.

But what I have come to understand, as the seasons unfolded, is that the Doctor’s most implacable enemy is not the Weeping Angels or the Daleks or the Cybermen or the Slitheen: it’s time.

From the minute the Doctor sweeps a new companion into the TARDIS, the clock starts ticking. He’s immortal. His human companions, not so much. He loves them as well as he can, for as long as he can, but always with the knowledge that, eventually, he will have to let them go….because what’s the alternative? Their lifespans are basically an eyeblink. As much as it hurts him, as much as he probably wishes he could keep them with him and have all of their time to himself, he knows he can’t.

Which makes “Doctor Who” both the best and the worst thing to be watching with a teenager who’s got one more year before she goes off into the world.

I’ve been thinking lately that middle age is one big de-acquisitioning phase; a decades-long series of goodbyes.

You spend the first half of your life getting things. You get a college degree and a career, a spouse, a house, a family. You get artwork for your walls and books for your bookshelves. You pile up accomplishments and kitchen gadgets. You end up with a closet full of clothes, a basement full of exercise equipment and old furniture, scrapbooks and photo albums.

And then you hit forty or fifty and you start losing things.

Maybe you lose a pet, or a parent. Maybe a marriage ends. At some point, your kids move out.

You downsize. You death clean. You consider all the objects you’ve acquired and ask if they spark joy, and whether anyone’s going to care about them when you’re gone. Maybe you consider all the things you’ve done and ask the same question. Did it make you happy? Did it serve anyone else? Will any of it matter, fifty or a hundred or thousand years from now? And how much difference did you make?

My mom, Fran, always believed that kids come into the world with their personalities basically formed. There’s not a lot parents can do to change who they are.

You love them. You support them. You give them every advantage you can. You do it, knowing you can’t make them into something they aren’t…and that, if you do your job right, you give them roots and you give them wings, and then you watch as they leave you.

“Everything’s got to end sometime,” the Doctor tells Amy, during one of the show’s Christmas episodes. “Otherwise, nothing would ever get started.”

My ending – or, the end of this stint of parenthood – is my daughters’ beginning. And I know it’s the best-case scenario, the way things are meant to happen. But sometimes I look at the loveseat and the purple Slanket, and think about the day (soon! soon!) when Phoebe will be texting or calling from wherever life takes her, and not sitting right there with me, and oh, it’s sad.

Not that I hope your kids are living with you in their middle age, but I am currently living with my mom and watching “The Sopranos” together. (She never watched it.) We never watched TV together until after I moved home the first time, after college. (It was “Law & Order” then.) It’s weirdly comforting to still be able to do this, despite all the financial instability that is the cause of me still living at home now, after years not.

I love your writing. Of course I enjoy your novels, especially the coming of age or family dynamics or women in the male gaze, etc.. but oof your essays and personal pieces; always erudite, immensely readable, and wise. Thank you.