If there’s one piece of advice you’ve probably heard about writing, it is this: show, don’t tell.

Don’t tell your readers a character is sad, or angry, or hungry, or horny – show us.

Sounds simple, right? But what does it look like in practice?

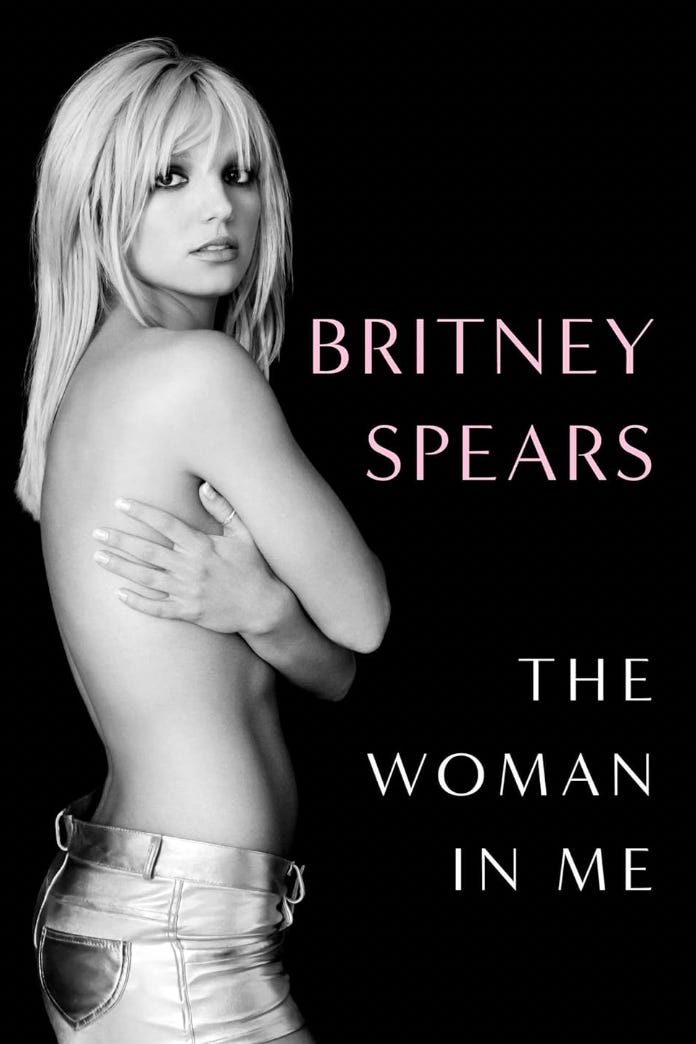

Like many of you, I downloaded Britney Spears’ autobiography THE WOMAN IN ME the minute it dropped. It’s a sad chronicle of a girl who was abused and mistreated by record-label executives, by boyfriends, and, worst of all, by her own family.

It’s bleak and sobering and hard to look away from…but, in some instances, it tells when it should show.

Big, all-caps disclaimer here: I am NOT TRYING TO BASH BRITNEY. In this house, we support Britney Spears! And, given that she’s already a top-notch singer/dancer/songwriter/provocateur, asking her to also be a first-rate writer is maybe a little unfair.

But, for our purposes, we can say it: the memoir should be so juicy, and yet, in places, it’s a little fleshless. A little dry.

Here is the book’s first sentence:

As a little girl I walked for hours alone in the silent woods behind my house in Louisiana, singing songs.

Solid sentence. Nice rhythm. But it feels like we’re being told a fact. We aren’t feeling the landscape, or what it’s like to move through them in a child’s body. We aren’t hearing the songs.

If I had been the editor, I would have pushed for more.

As a little girl (how old were you?) I walked for hours (how many? What time of day?) alone in the silent woods (are we talking the forest primeval, or vacant lots in a subdivision? What kind of trees? What can you smell? What can you hear – because woods aren’t ever completely silent, right?) behind my house in Louisiana (where in Louisiana are we, and what kind of house?) singing songs (which ones?)

Imagine that sentence, with some of those blanks filled in:

As a little girl I loved walking in the woods.

I don’t remember how old I was, but it was before I’d started kindergarten, when my days were long and formless, without the rhythms imposed by classrooms and clocks. I’d slip out the back door of our small split-level brick house and amble for hours, through the mid-morning, past lunchtime, straight into the afternoon. The woods began where our backyard ended, and stretched on for miles, sloping gently down toward the Taxahatchee River. The leafy branches would diffuse the sun’s heat, and the world seemed to doze in the morning’s warmth, quiet except for the sound of my sneakers slipping over the hard-packed dirt. A whippoorwill calling, a squirrel, scampering off through the underbrush.

To this background, I would add my own little-girl voice, singing “What A Friend We Have in Jesus,” and other hymns I’d learned in church.

Maybe that’s a little long, though. Second drafts – at least, in my experience -- are when things get bloated. You’re throwing in every detail that fits, and some that don’t.

Let’s try setting the mood faster and getting to the point.

As a little girl, before I’d started kindergarten, when the days were still long and unformed, I would spend hours walking in the woods that began where our backyard ended. I’d slip out of the house early in the morning. My dad would be at work; my mom would be sleeping, and the world was quiet except for the sound of my sneakers slipping over the hard-packed dirt; a whippoorwill calling, a squirrel hurrying through the underbrush.

To this background, I would add my own little-girl voice, as I sang the hymns I’d learned in church.

Even pared back, you can see how the details help the scene come into focus. The writing isn’t going to win any prizes, but pay attention to what we can do with language: the consonance of sneakers slipping and handful of hymns, the internal rhyme of slipping and whipporwill, squirrel and hurrying.

It’s easy to add detail when you’re talking about something concrete – a house, a forest, a time of day. You ask: how does it look? How does it sound? How does it smell, feel, taste? And you try to express that in fresh, evocative ways.

It is harder when you’re talking about feelings.

Take this sentence: “When I was growing up, my mother and father fought constantly. He was an alcoholic. I was usually scared in my home.”

This sounds like something a healthcare worker would write on an intake form. Father alcoholic. Parents fighting. Patient reports being scared.

I understand that this is painful, personal stuff. The fact remains: readers want to know more than just what happened. They want to know how it felt. They want texture, nuance, details. It’s your job as a writer to add them.

Compare the first version to this:

When I was growing up, my mother and father would have terrible fights. They’d start arguing in the kitchen, move into the living room, and end up their bedroom, their voices getting louder as they went. I remember how my father seemed to enlarge with anger, how a brick-red flush would creep up his neck, how his black hair seemed to bristle and his body seemed to swell, until he looked, to my eyes, like a giant, his head scraping the ceiling, workboots making the floor shake.

If my father grew, my mother shrank, cringing away from him in her thin button-down blouses and high-waisted jeans, shoulders hunched, face downcast. When they fought, it seemed like he was a giant, and she was invisible…or at least, too small to save me. Too small to save herself.

I have no idea if any of these details are correct. I don’t know what color Jamie Spears’ hair is, or what he drank, or if Britney’s mom wore thin blouses and jeans. But do you see how the second version feels more true? And how much more poignant it is than just saying My dad drank, my parents fought?

And then we get to Justin Timberlake, and the writing feels similarly thin.

“In my personal life, I was so happy. Justin and I lived together in Orlando. We shared a gorgeous, airy two-story house with a tile roof and a swimming pool out back.” And, later, “That was a good time in my life. I was so in love with Justin, just smitten.”

It’s always hard to write about love in a way that feels fresh and cliché- free. Smitten is a hard state to describe, and language is an imperfect vehicle. But, again, details are the answer.

Compare “I was so in love with Justin,” to this, from Audrey Niffeneger’s THE TIME TRAVELER’S WIFE:

“And Clare, always Clare. Clare in the morning, sleepy and crumple-faced. Clare with her arms plunging into the papermaking vat, pulling up the mold and shaking it so, and so, to meld the fibers. Clare reading, with her hair hanging over the back of the chair, massaging balm into her cracked red hands before bed. Clare’s low voice is in my ear often. I hate to be where she is not, when she is not.”

Those are quotidian details – a woman waking from sleep, doing her job, rubbing lotion into her hands skin before bedtime. But they’re observed with a lover’s eye, recounted in a lover’s voice, if that makes sense. The person telling us about Clare sees her. He notices every little thing. That’s how we know they’re in love.

And here’s the thing: I know Britney – or maybe one of her ghostwriters – has it in her, because of this passage about a neighbor’s rock garden, “full of small, soft pebbles that would trap the heat and stay warm in a way that felt so good against my skin. I would lie down on those rocks and look up at the sky, feeling the warmth from below and above, thinking: I can make my own way in life. I can make my dreams come true.”

I have no idea how a pebble can be soft – small, yes; rounded, sure. Soft? Not so much. Still, that is a lovely, specific image, and a beautiful wish, and it’s devastating when you see, for the next two hundred or so pages, how it does and does not come true.

Thanks for reading! And please come back, and bring your friends. Next time, we’ll move on to another celebrity memoir and talk about the importance of voice – and how to find your own.

What a wonderful article, Jen, and full of concrete example that I can apply to my own writing. I am certainly guilty of more telling than showing more times than I'd like to admit. I will be watching like a hawk for your next piece! :)

Annabelle Tometich's memoir "The Mango Tree" has such good writing about a child witnessing a parents' fight -- I felt trapped reading it